The fall of Bali and the naval battle of the Badoeng Strait

18 - 20 of February of 1942

By: Felipe C. Ramires

Strategic context

The island of Bali is considered to be one of the best tropical paradises of

the Indonesian archipelago. Located in the Lesser Sundas archipelago, with the

Indian Ocean to the south and the Flores Sea to the north, this small volcanic

island of 5591 Km2 is situated only a few miles off the eastern coast of the

island of Java. It gives any visitor an excellent exotic-tropical environment,

very important traces of the ancient Indonesian Hindu civilisation, small and

magnificent beaches like the Beach of Kuta and the warm waters of the Bali,

Badoeng and Lombok Straits. However, most people would never imagine that in

one day, those beaches would be the stage of the disembarkation of the Japanese

invaders and that soon after these calm waters would be the scene of the second

naval battle fought between the Allied forces (ABDA) and the Japanese strike

forces, in the first phase of the Pacific Campaign.

After the Pearl Harbour attack on the 7th of December of 1941, all the Japanese

armed forces initiated an expansion campaign to all Southeast Asia, Philippines

and the Indonesian archipelago, an expansion that would be known as the Japanese

"blitzkrieg". The recent and badly organised Allied force (ABDA), formed

to put up some resistance to the Japanese tentacles, could do little or nothing

to stop it and besides that it suffered heavy casualties in the air, land and

sea. The Japanese ambition and the desperate necessity of getting raw materials

(oil, rubber and timber), in abundance from the region, were the principal motivation

that led the Japanese Empire to take this initiative, later crowned with success.

On the 10th of February 1942 the Japanese completed the conquest of the island

of Borneo with the capture of Bandjarmasin and with the securement of an airfield

at Balikpapan. Makassar and Kendari in the Celebes islands were taken respectively

on the 8th and the 10th of February and they could give them excellent naval

and aerial support bases. On the 14th of February another Japanese disembarkation

occurred on the west coast of Sumatra Island, the oil refineries and the air

base of Palembang secured in this island formed another strong support base

for the next attacks. The island of Java, where the great part of the Allied

forces were concentrated, was the main target and since it was already surrounded

from the west and north it was needed to do it also by east. Bali then became

involved in this strategic context and it was more then vital to the Japanese

to take over the island to secure a final offensive with success.

Beyond the geographic proximity of Java, the island of Bali also interested

the Japanese with the fact that there was one important airfield in Den Passar,

the biggest city in the island. Even occupied by the Dutch it was more than

essential to take the airfield intact because it could give an excellent capacity

of aerial support and control in the involved zone. It would be easier for the

Japanese to set off air raids to Soerabaja and to Tjilatjap, important Allied

naval bases, and to the Allied airfields of Blimping, Perak and Madaen. The

already taken airfields of the Borneo and Celebes islands could do the same

function but due to the great distance and to the adverse climatic conditions

the flight operations in these bases were much more limited. Bali offered much

dryer weather and other favourable conditions to a continuous aerial support

campaign. There was also the necessity of interception of the current Allied

fighter flights from Australia to Java and with one fighter-interception force

at Bali it would be much easier for the Japanese to block these fighter reinforcements.

By the other side, the existence of such aerial support could give also, in

certain forms, a good security for the Bali, Badoeng and Lombok Straits. The

occupation of Bali was exclusively strategic and in spite of offering almost

nothing to the development of the Japanese Empire it was more than essential

it be captured.

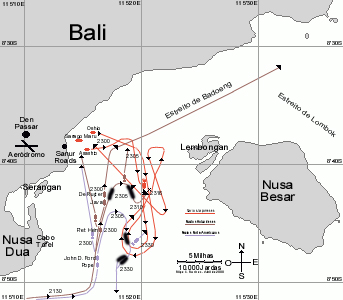

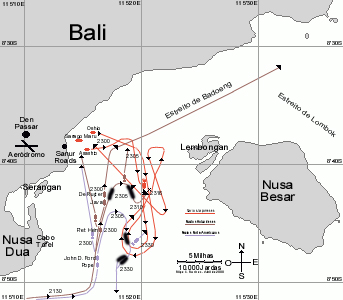

The Disembarkation at Sanur Roads and the disposition of the forces

In order to realise such a daring operation the Japanese moved to build up

a plan for the invasion of Bali, this being the first part of the final strike

operation against Java. On the 17th of February the Japanese already had concentrated

in Makassar a small naval force for this invasion and it consisted of two troop-transport

ships that would carry out the disembarkation, the Sasago Maru and the

Sagami Maru. The close escort of four destroyers, the Asashio, Oshio,

Arashio and Michishio, protected them. To support this force, if

necessary, there was the light-cruiser Nagara and his own three destroyers.

Hatsushimo, Nenohi and Wakaba would follow some distance behind,

staying in patrol stations in the north entrance of the Badoeng and Lombok Straits,

in the case of possible ship or submarine attacks from the ABDA forces. All

this force was co-ordinated on the bridge of the Nagara by the Japanese

Rear-Admiral Kyuji Kubo as it would have been strategically unsound to involve

the two joint naval forces in the small straits east of Bali; they would certainly

get more difficult to manoeuvre in the case of battle and they would offer more

targets to possible air and naval strikes of the Allies. During the travel that

the naval forces would make between Makassar to Bali they would be protected

by the air cover of A6M Zero fighters of the 3rd Air Group and from Tainon Air

Group, based in Makassar, to eliminate the chances of a successful Allied air

raid during the crossing of the Flores Sea.

The area chosen for the disembarkation at Bali was the small beaches near Sanur

Roads, in the southeast coast of the island and very near to Den Passar which

meant that the Japanese when disembarking should take the airfield as the main

objective. To proceed to the disembark and to the land advance in Bali were

detached some experienced forces from the Philippines part of which were the

48th Infantry Division, one regiment of the 1st Infantry Division of Formosa,

almost all the 3rd Battalion, one platoon of mountain artillery, one platoon

of engineering and some radio and logistic units. The Japanese were ready for

combat and their naval forces left Makassar on the night of the 17th to 18th

of February, heading for Bali.

The distance between Makassar and the disembarkation point was made without

incidents to the Japanese with only the sporadic presence of the allied reconnaissance

planes. The Japanese force arrived to the Badoeng Strait on the night of the

18th to 19th of February beginning the disembarkation in Sanur Roads from 0200

hours of the 19th of February onwards. The resistance offered by the 600 native

militiamen was little or none since they defected almost immediately. Meanwhile

to join the chaos, internal communication problems between the Dutch officers

and defenders lead them to not destroy the airfield, a task that should have

been carried out so that the airfield did not fall in the Japanese hands. This

meant they captured the airfield complex completely intact. At 1030 of 19th

of February the airfield was totally secured and the land advance through the

island proceeded, the goal was taken and the Japanese achieved one more magnificent

strategic victory.

However, as I already

said before, the Japanese force was detected by the Allied air reconnaissance

and calculating their destination they soon they realised that Bali was to be

invaded. In certain forms anticipating an attack to this island, the ABDA forces

had already detached to patrol the Badoeng Strait the American submarine USS

Seawolf and to patrol the north entrance by the Flores Sea the British submarine

HMS Truant was on the way. Meanwhile the Japanese continued with the division

of their forces with the disembark force entering through the straits of the

island and the backup force remaining on patrol on the Flores Sea. Incredibly

the two Allied submarines were each one of them in the same zone of one of the

opposing Japanese forces. The first to make contact was Seawolf that

detected the main force already disembarking at 0200 of the 19th of February.

The American submarine tried to make a surface attack but it was spotted by

the Japanese destroyers and forced to dive. The navigation in the strait was

precarious because the submarine didn't know the area well and ran aground in

the bottom of the strait for some time. After some attempts and frustrations

the submarine came to surface but once again it was spotted by the Japanese

escorts that advanced to attack it. In the retreat of the zone at full speed

the Seawolf fired two torpedoes from the stern tubes but they missed

the targets and exploded against the coast of Bali. Meanwhile, at the same time

that Seawolf escaped, the Truant arrived to the north area of

Bali, where the support force of Kubo was. The British submarine managed to

get close enough to this force to fire six torpedoes against Nagara but

without any impact. Discovered and pursued by the Nagara escorts, the

Truant also retreated, to Soerabaja.

However, as I already

said before, the Japanese force was detected by the Allied air reconnaissance

and calculating their destination they soon they realised that Bali was to be

invaded. In certain forms anticipating an attack to this island, the ABDA forces

had already detached to patrol the Badoeng Strait the American submarine USS

Seawolf and to patrol the north entrance by the Flores Sea the British submarine

HMS Truant was on the way. Meanwhile the Japanese continued with the division

of their forces with the disembark force entering through the straits of the

island and the backup force remaining on patrol on the Flores Sea. Incredibly

the two Allied submarines were each one of them in the same zone of one of the

opposing Japanese forces. The first to make contact was Seawolf that

detected the main force already disembarking at 0200 of the 19th of February.

The American submarine tried to make a surface attack but it was spotted by

the Japanese destroyers and forced to dive. The navigation in the strait was

precarious because the submarine didn't know the area well and ran aground in

the bottom of the strait for some time. After some attempts and frustrations

the submarine came to surface but once again it was spotted by the Japanese

escorts that advanced to attack it. In the retreat of the zone at full speed

the Seawolf fired two torpedoes from the stern tubes but they missed

the targets and exploded against the coast of Bali. Meanwhile, at the same time

that Seawolf escaped, the Truant arrived to the north area of

Bali, where the support force of Kubo was. The British submarine managed to

get close enough to this force to fire six torpedoes against Nagara but

without any impact. Discovered and pursued by the Nagara escorts, the

Truant also retreated, to Soerabaja.

On the other side, knowing already of the presence of one Japanese force disembarking

in Bali, the ABDA forces grouped a small force of bombers of the USAAF composed

of thirteen B-17 high altitude bombers and by seven A-24 dive bombers, without

any escort of fighter planes (due to the absence of this kind of planes). The

force's take-off from the airfields at first light of the 19th and arrived at

Bali at 0700 of the same morning. Incredibly the Allied planes weren't attacked

by the Japanese beyond the weak opposition of their few anti-aircraft guns and

they proceeded to bomb the invasion force. The Allied planes completed their

mission and returned to their bases where they exaggeratedly announced that

they got four direct hits and twelve near-misses, also relating the presence

of heavy cruisers and other heavy tonnage warships supporting the disembarkation

that in reality weren't there. The reality was that they didn't get more than

one direct hit on the transport Sagami Maru engine room.

Apparently everything ran well for the Allies. It was supposed that the Seawolf

and the Truant managed to get some success and the bombers reports indicated

that many Japanese ships were damaged or even sunk. However, to get one such

necessary and complete Allied victory it was evident that they should send a

naval strike force to temporarily put an end to the Japanese menace around Java.

As soon as the Japanese disembarking

in Bali was known, in the early morning of the 19th of February, the Allies

already had formed a plan and a naval force to attack the Japanese force. In

the lead of the Allied force was the Dutch Admiral Karl Doorman who in spite

of great difficulties and a short response time managed to group one small naval

force of three light-cruisers, eight destroyers and nine torpedo-launchers.

Nevertheless the force had to divide because of early naval operations preceding

this one, so Doorman had to move with his forces separately. In Tjilatjap was

formed the first strike force which used the Dutch light-cruisers De Ruyter

and Java, the Dutch destroyers Kortenaer and Piet Hein

and the American destroyers John D. Ford and Pope. The second

wave was made up of the Dutch light-cruiser Tromp, in Soerabaja, that

was waiting for the reinforcements of the American destroyers of Destroyer

Division 58, the Stewart, John D. Edwards, Parrott and Pillsbury,

that were coming from Ratai Bay, in the south of Sumatra. A third force of nine

torpedo-launches (TM-4, TM-5, TM-6, TM-7, TM-9, TM-10, TM-11, TM-12 and TM-13)

would leave from Soerabaja and assist the second wave in the final attack.

As soon as the Japanese disembarking

in Bali was known, in the early morning of the 19th of February, the Allies

already had formed a plan and a naval force to attack the Japanese force. In

the lead of the Allied force was the Dutch Admiral Karl Doorman who in spite

of great difficulties and a short response time managed to group one small naval

force of three light-cruisers, eight destroyers and nine torpedo-launchers.

Nevertheless the force had to divide because of early naval operations preceding

this one, so Doorman had to move with his forces separately. In Tjilatjap was

formed the first strike force which used the Dutch light-cruisers De Ruyter

and Java, the Dutch destroyers Kortenaer and Piet Hein

and the American destroyers John D. Ford and Pope. The second

wave was made up of the Dutch light-cruiser Tromp, in Soerabaja, that

was waiting for the reinforcements of the American destroyers of Destroyer

Division 58, the Stewart, John D. Edwards, Parrott and Pillsbury,

that were coming from Ratai Bay, in the south of Sumatra. A third force of nine

torpedo-launches (TM-4, TM-5, TM-6, TM-7, TM-9, TM-10, TM-11, TM-12 and TM-13)

would leave from Soerabaja and assist the second wave in the final attack.

Other ships could have joined with this force but for many reasons were unavailable

to this operation. The American destroyers Barker and Bulmer were

at Tjilatjap but they were damaged by the air raids of the 14th of February,

so they were going to be detached to Australia for repairs. The Dutch destroyers

Witte de with and Banckert were also in need of overhaul and damage

reparations and because of that they couldn't proceed to the attack. The Dutch

destroyer Evertsen and various British destroyers were escorting a troop

convoy through the Sunda Strait and were fighting at the same time the menace

of the Japanese submarines. Lastly, the American heavy-cruiser Houston

was also escorting a troop convoy from Darwin to Kupang, in the Dutch Timor,

and would take much time to arrive to Java.

The attack plan improvised by Doorman followed practically the same strategy

adopted by the American destroyers in the Battle of Balikpapan (24th of January

of 1942), that is; the Allied strike forces should be positioned between the

Japanese disembarkation lines. The initial attack was done by the artillery

of the light-cruisers, at point blank distance to inflict the maximum of damage

in a small space of time. After that the destroyers would follow with one torpedo

attack. Nevertheless, it was attributed to each one of the Allied forces one

specific function during the operation. The first force (light-cruisers De

Ruyter and Java, destroyers Kortenaer, Piet Hein, John D. Ford

and Pope would enter by the south of the Badoeng Strait and would attack

first with artillery and then with torpedoes, retreating after that to the north

of the strait. The second force (light-cruiser Tromp and destroyers Stewart,

John D. Edwards, Parrott and Pillsbury) would also enter by south

and should made a torpedo attack first with the Tromp giving artillery

support later. Finally, the third force of the nine Dutch torpedo-launches would

arrive shortly after that to attack the already damaged ships, with torpedoes.

The Allied force was far superior to the one that made the attack in Balikpapan

and all reports indicated that the submarine and air strikes had already damaged

the Japanese ships. The plan apparently was to be crowned with success and expected

to be an equal or even superior victory to the one for Balikpapan.

The first phase of the battle

Ready and lithely organised the first Allied strike force steamed from Tjilatjap

on the night of the 18th of February. But bad luck started to affect this naval

formation when it was leaving the harbour, the Dutch destroyer Kortenaer

lost rudder control for a time and ran aground in one of the channel shores.

It was impossible for the Dutch ship to return to the formation and they had

to wait for the next morning tide to free the ship, Doorman had to proceed with

the mission without this ship due to the time factor. Kortenaer had to

go to Soerabaja for the repair of such damage and wouldn't participate in this

action while the rest of the force steamed for Bali at 25 knots.

However, on those precise moments the Japanese disembarkation force had already

initiated their final mission and dealt at the same time with the Allied submarines

and bombers. Kubo was conscious of his vulnerable position and ordered to hurry

up the operation. Emergency repairs to the transport Sagami Maru were

made and at 2200 of the 19th of February the ship could sail and accompanied

by the Arashio and Michishio steamed for Makassar. The support

force leaded by the Nagara also reversed course and steamed for Makassar

too. In Sanur Roads only remained the transport Sasago Maru and the destroyers

Asashio and Oshio, which should collect the remaining Daihatsu

disembarkation launches, used in the attack of Bali.

While the Japanese made these movements, the first Allied force was arriving

in Bali. At 2130 of the 19th of February such force was sailing off Nusa Dua,

in the south extreme of Bali and was getting ready for combat. The battle formation

line was made with the De Ruyter and Java in the lead; followed

by the Piet Hein 5500 yards behind them and at the same distance from

the Dutch destroyer were the John D. Ford and the Pope. The speed

was raised to 27 knots and the Allied ships started to enter in the Badoeng

Strait. The sea was calm, the night was very dark and there was almost no wind,

the ideal scene for a night battle. At 2300, already inside the strait, Java

spotted the three Japanese ships at starboard (Sasago Maru, Asashio

and Oshio) that had already finished their mission and were preparing

themselves to leave to Makassar. Immediately the Java fired starshells,

to improve visibility, and then opened fire against Asashio at the point

blank range of 2200 yards. In the other side, De Ruyter with her artillery

pointed to portside took some time to open fire but as soon it was possible

made it against Oshio.

The Japanese destroyers were surprised but illuminated the area and with readiness

disposed themselves to protect their transport charging in an eastern course

against the Dutch cruisers. These last ones seeing that Asashio and Oshio

intended to cross their "T", changed course to the northeast with the objective

of clearing the area and to find other targets to the north, without success.

Although they didn't fire more then ten salvos, each one of the Dutch cruisers

claimed many impacts in the enemy destroyers (probably only a few near misses)

as the Japanese ships proceeded with their mission apparently without damage.

The Asashio managed to put one 5' projectile in Java but little

damage was done. The cruisers retreated at high speed and the Japanese destroyers

lost contact steaming now for southeast.

Meanwhile the Piet Hein also entered the scene and seeing that the Dutch

cruisers were engaging the Japanese destroyers, fired three torpedoes against

Sasago Maru opening fire with the 4.7' artillery against the same target.

However, free from the fire of the cruisers, the Asashio and Oshio

closed in to the Piet Hein firing against the Dutch ship. Faced with

this menace, at 2305 Piet Hein turned to starboard in a southeast course

launching two torpedoes against Asashio that would miss while simultaneously

firing the artillery and at the same time creating a smoke screen to camouflage

itself from the Japanese ships. At 2310 Asashio, at the close distance

of 1000 yards, hit it with two 5' shells, one in the second mast platform that

caused a great fire, and the other in the second boiler room. Immediately Piet

Hein was forced to stop due to the absence of propulsion and at same moment

was hit many times by the 25mm anti-aircraft guns of Asashio as it closed

in even more and launched torpedoes. Oshio also launched itself to this

unfair fight and fired torpedoes from its own side. Although heavily damaged,

Piet Hein managed to get some propulsion at 2316 but one of the Asashio's

torpedoes hit the ship at portside and it sunk almost immediately with great

loss of human life.

Piet Hein's destiny was sealed forever and again the unstopped Asashio

and Oshio advanced for the third time against the Allied ships. Piet

Hein's loss has raised in many studies, including the one I made, a few

questions related to the reasons that forced the ship to stop. Officially Asashio

hit the ship but it is also highly probable that the Dutch ship was an accidental

target of the American destroyers that followed it. Possibly the latter had

briefly lost contact with Piet Hein and suddenly sighted one unknown

destroyer steaming in the opposite direction while launching a smoke screen.

Obviously that they would have faced it as an enemy ship dissimulating the Japanese

transports and opened fire with their 4' guns against it, until they really

understood the true identification of the ship, probably too late. The fact

is that the causes of the damages and of the Piet Hein's sinking were

totally attributed to Asashio and any other possibilities were conveniently

forgotten.

However the battle continued for some time. At 2300 like the Piet Hein,

the John D. Ford and the Pope fired their portside torpedoes

against Sasago Maru, (they would also miss), following with the fire

of their 4' artillery, and shell hits were claimed in the transport. But at

2305 they watched one destroyer (Piet Hein) making smoke and "charging"

against them and that made them to closed in of it, raising the speed to 29

knots. When Piet Hein was hit, the American destroyers checking the real

identification of the ship rapidly steamed to assist it but they never would

arrive in time because it was sunk at 2316. The smoke screens made by the Dutch

destroyer hid Asashio and Oshio so they weren't detected by the

American destroyers that were closing in. When they passed through the Piet

Hein's smoke screen the American destroyers sighted Asashio, which

immediately opened fire at 2324 against John D. Ford. Although retaliating

with their artillery and with five torpedoes from Pope, without success,

the two Allied ships were forced to retreat to southeast making smoke simultaneously.

Attempts to set course to north were frustrated by the pressure of the Japanese

ships and by the torpedoes launched by them. Also Oshio entered the fight,

a fact that certainly forced the two American ships to abandon the area forever

to sail south, with the cover of another smoke screen, at 2330, without any

damage suffered or inflicted on the enemy. Asashio and Oshio lost

visual contact with the American ships and for a few minutes they exchanged

artillery salvos thinking each was attacking another Allied ship. Suffering

no damage, soon after that they would discover the error and join once again

to defend and assist the damaged Sasago Maru. Both Japanese destroyers

claimed the sinking of one Allied ship, improbable credit exception for the

Asashio that sunk Piet Hein. Meanwhile as soon he knew of the

sighting of Allied ships in the Badoeng Strait, Admiral Kubo ordered that Arashio

and Michishio leave the Sagami Maru to help the two other destroyers,

but they only arrived at the end of the second phase of the battle. By is own

side the Nagara force inverted again course and was steaming also to

join the same ships involved in the battle. At last, Asashio and Oshio

assisted Sasago Maru, probably damaged by the 4.7 shells of the Piet

Hein or by the 4' shells of the John D. Ford and Pope, they

reloaded their torpedo-tubes and were getting ready for the eventual second

Allied attack that it was on its way.

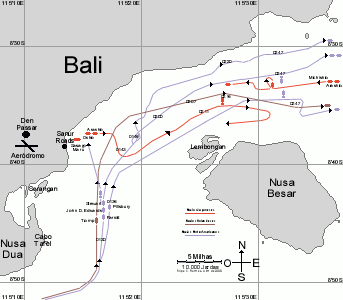

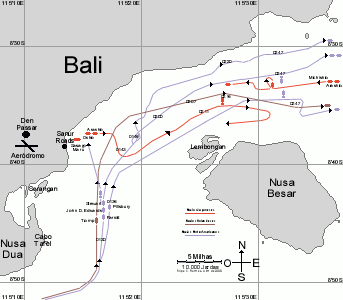

The attack of the second wave

To complete the mission of the first strike force, the second allied naval

formation sortied from the naval base of Soerabaja at the end of the afternoon

of the 19th of February, having estimated her arrival in the Badoeng Strait

in early morning of the 20th of February. Also this force was only able to leave

after the arriving and refuelling of the four American destroyers, coming from

the south of Sumatra. Contrary to the first force, bad luck didn't affect this

small formation and they carried on to the short travel between Soerabaja and

Bali without major problems. The force crossed the Bali Strait, surrounded the

south part of the island and at 0109 of the morning of the 20th of February

they were getting ready to enter in the Badoeng Strait. Then they proceeded

to battle line formation leaded by the Stewart, followed by the Parrott,

Pillsbury and by John D. Edwards, backwards was Tromp that

would support the charge of the destroyers with its 5.9' artillery. Speed was

raised to 28 knots. Radio silence was maintained and at the time news from the

first striking force was unknown, so, the second wave prepared to launch it

self into the Badoeng Strait not knowing the battle conditions.

However at 0130 the Allied ships were partially sighted by the Japanese ships

trying to identify the new intruders with light signals of Morse code. Unknowing

the position of the preceding strike force the Allied ships of the second wave

stained for moments confused about the intention of those signals. Ignoring

the chance of being friendly and trying to communicate with them, the Allied

force faced this challenge as being from the Japanese ships. So at 0136 the

Allied ships answered to the light signals, but with torpedoes. The Stewart

and the Parrott fired each one of their six portside torpedoes while

the Pillsbury fired only three. Incredibly all fifteen torpedoes missed

or were avoided by their targets. On the other side, Asashio and Oshio

seeing and avoiding the torpedoes wakes, couldn't get better confirmation that

in reality the unknown ships were enemies and once again they were going to

be attacked. Brief silent moments followed as the opposing forces were closing

against each other waiting for any moment to attack the enemy ships. Tension

raised when at 0143 Stewart spotted the two Japanese destroyers at portside.

Immediately it turned on and pointed their searchlights, firing with their 4'

guns against Oshio. Equally all the other three destroyers opened fire

and even John D. Edwards came to fire two torpedoes (that would miss),

however, other two were stuck in the tubes. Meanwhile, the Japanese answer was

quite immediate and with terrible efficiency, since Asashio's first salvo

straddled Stewart and the second one hit it with two 5' shells. At 0146

one shell from Asashio hit Stewart but slipped away and then another

shell penetrated the hull and hit the steering room, killing one sailor and

wounding one officer. The result was the damaged Stewart briefly lost

control and literally forced the other Allied destroyers to make evasive actions

to avoid collision.

Chaos was implanted in the Allied formation, by close that Parrott didn't

collide with the Stewart; Pillsbury was already steaming in one parallel

course to starboard as the battle begun. John D. Edwards had to violently

manoeuvre to starboard to avoid the Parrott, taking part again of the

formation short after that following the Stewart. Blocked from charging

against the disembark anchorage the Allied ships retreated to northeast with

the Asashio and the Oshio "tailing them". By that time the American

destroyers made another formation at 0200 as they retreated to northeast. Stewart

had recovered control and steamed now behind John D. Edwards, with the

Parrott steaming near the coast in a portside parallel course to them, Pillsbury

having moved away and steamed alone to starboard of the formation with the Tromp

following it 3000 yards behind. On their side Asashio and Oshio

had cut across the Allies course from behind and chased them starboardside,

trying to isolate and attack Pillsbury, unsuccessfully. At the same time

Tromp prepared itself to enter in the fight and raised the speed to 31

knots. Shortly after that the cruiser sighted at starboard Asashio and

Oshio trying to identify this strange ship by changing light signals.

Tromp answered by opening fire with their 5.9' guns against Oshio

and with their 40-mm anti-aircraft guns against Asashio. However

the ship committed the fatal mistake of turning on and pointing the searchlight

against the Japanese ships that now, knowing of Tromp's presence, had

one excellent aiming point for their artillery. So at 0207 one enormous "rain"

of 12 shells of 5' fired from Asashio hit them. One damaged the fire

control of the portside torpedo tubes, another destroyed the artillery director,

another nine hit the bridge and the surrounding area and one last one hit the

Dutch cruiser below the waterline, causing a brief flooding. At the same time

Oshio fired a spread of three torpedoes against the cruiser that managed

to avoid them closely, at 0216. With 10 dead and with 30 wounded, the damaged

cruiser continued to give fight to the Japanese destroyers, even to firing their

artillery manually and locally, successfully hitting both Oshio and Asashio.

At 0211 Oshio was hit between the bridge and in one of the portside torpedoes

magazine by one 5.9' shell but so close that there was no secondary explosions

that certainly would have sunk the ship. The result of the impact reflected

in 7 dead in Oshio's crew. Almost simultaneously many 40-mm shells hit

Asashio from Tromp that would destroy their searchlight platform

and cause 4 dead. Soon after that the Japanese ships and the Allied ships lost

contact mutually. Asashio and Oshio returned back to Sanur Roads

to assist and to protect the Sasago Maru. Tromp recovered from the fight

and returned for formation staying behind Pillsbury. Meanwhile Parrott

temporarily run aground at 0220 and manage to free itself but didn't participate

any more in the battle. John D. Edwards and Stewart steamed in

formation and like the other Allied ships were desperately running to northeast.

Nevertheless there was one surprise waiting for them and at 0247 Stewart

detected two ships steaming to southwest, in one opposite course of the

Allies. These were the Michishio and Arashio that left Sagami

Maru and came now in assistance to Asashio and Oshio. However

these two Japanese destroyers ignored the composition and the position of the

Allied force and accidentally put themselves exactly between the column of Pillsbury

and Tromp and the column of John D. Edwards and Stewart.

Immediately Stewart turned on and pointed the searchlight against Michishio

firing with their artillery and with the six starboard torpedoes, John

D. Edwards followed the example and equally fired their artillery and their

six starboard torpedoes. In the other side Pillsbury also fired their

remaining three portside torpedoes and teaming with Tromp fired against

the Japanese. The surprised Japanese destroyers could do little or nothing to

respond successfully against John D. Edwards and Stewart. To escape

the Stewart's searchlight, Michishio changed course to north but

suddenly it was hit by an enormous amount of shells. John D. Edwards hit

it and destroyed Michishio in the engine room while Pillsbury and

Tromp hit it in the anti-aircraft guns platform amidships and in the

bridge. Michishio was immediately immobilised and crippled with 13 dead

and 83 wounded aboard. Arashio seeing the disadvantage of their position

rapidly retreated to west staying undamaged in this brief fight.

Nevertheless, as had happened during the whole battle, all the torpedoes fired

by the Allies missed the targets, even at close range. Both opposite formations

weren't too much interested in returning to fight and rapidly search to retreat

each one of them for their own side. The allied force retired from the Badoeng

Strait and during the morning steamed along the north coast of Bali, where they

were attacked unsuccessfully by 9 Japanese bombers from Makassar and incredibly

were not found by the Nagara force, saving them another combat. They

would arrive at Soerabaja on the night of 20th of February without further problems.

Meanwhile, the Japanese force still remained for some time in the Badoeng Strait

and Asashio had to tow the damaged Michishio at the same time

that Arashio and Oshio continued to protect Sasago Maru,

on the way back to Makassar.

Relatively to the attack of the third wave, formed by the nine Dutch torpedo-launches,

such force sortied from Soerabaja in the morning of the 19th of February when

the second strike force was already on the way. However this formation initially

had some bad luck and when leaving the naval base of Soerabaja the TM-6

collided with one of the light buoys of the harbour and couldn't proceed to

the mission because of the suffered damage. The remaining eight launches steamed

to the Badoeng Strait, by the Bali Strait, as had the second wave. A stop in

Pangpang Bay to be refuelled by one Dutch auxiliary ship was required and then

they steamed very quickly to the Badoeng Strait to arrive shortly after the

second force had retreated. They positioned themselves near Lemblogan Island

to review the combat formation. Split in two groups of four, the Dutch torpedo-launches

advanced to the centre of the Badoeng Strait and to Sanur Roads. The first group

approached off the coast and to the anchorage but detected no Japanese ships.

However the second group, steaming almost at 8000 yards of it, detected one

Japanese destroyer (probably Oshio or Arashio) heading south at

high speed. Even with raising the speed to 30 knots the torpedo-launches of

the second group never reached a favourable attack position. Frustrated in their

attack the two groups rejoined again and steamed back to Soerabaja by the same

course, being again refuelled at Pangpang bay. The naval battle of the Badoeng

Strait was finally over.

Conclusion

In the first place, the battle of the Badoeng Strait should never have happened,

not in the way that was made and not with the conditions in which it was realised.

Doorman's plan completely changed when the battle took place. The Allies achieved

everything but the wanted surprise factor, when opening fire the Dutch light-cruisers

renounced the possibility of one eminent surface attack. Also the Dutch gunners

failed completely to damage or sink the only ships that could offer them some

resistance, Asashio and Oshio. The Japanese ships were without

doubt surprised by the attack of the cruisers but their great training capabilities

in night combats enabled them to respond to the attack. Apart from the Java

being hit by one 5' shell, the Dutch light-cruisers had many lucky moments

in this initial phase of the battle, their quick retreat was well pondered and

avoided further damage, and saved them from becoming victims of a torpedo attack.

On the other hand, Piet Hein was completely inevitable. The Dutch destroyer

should never have become isolated in the battle. The Japanese had inferior numbers

during the battle but in that small moment Asashio and Oshio come

across with Piet Hein they achieved a small superiority and from there

they took great benefit when attacking and sinking the Dutch ship. Piet Hein

should have entered in the fight accompanying the Dutch light-cruisers or

the American destroyers. Following these way results probably would be different.

After that, the procedure of the John D. Ford and of the Pope

may be considered correct, in spite of having no success, they launched torpedoes

first, then attacked with their artillery and when coming across the furious

combat tenacity of the Japanese destroyers opted well to retreat to south. This

decision was criticised by many but if the two American ships really had proceeded

to north they certainly would have been positioned between the two Japanese

ships and doubtfully that they would be submitted to cross fire and to torpedo

spreads. Probably, their destiny would be the same of the Piet Hein.

The attack of the second wave was percentage wise much more successful. The

initial attack with torpedoes was decisive but all the torpedoes (Mk8) were

avoided or failed to explode against their targets. Certainly if their warheads

had detonated against the three Japanese ships the battle would have ended in

that moment. However such didn't happen and Asashio and Oshio

faced again a far superior Allied force. The Stewart suffered damage

that could have happened to any ship present in the battle, even to the Japanese,

simply the gunners of the latter were more accurate. The damage that the Tromp

susustained was inexcusable. The Japanese didn't know of the presence of this

ship until the moment that it turned on the searchlight. With much luck none

of the hits of the shell rainstorm that the Tromp received affected the

propulsion equipment of the ship and for close the Dutch light-cruiser wasn't

victim of a torpedo spread that certainly would have sunk the ship. On the other

side, the Japanese gunfire had damaged Tromp's bridge, gun director and

starboardside torpedo tubes reducing significantly the cruisers combat capacity.

Had the Tromp hit Oshio with one 5.9' shell using local and manual

gun direction imagine what would have happened to the Japanese destroyer if

the gun director of the Dutch light-cruiser was still operational, probably

it would be reduced to a flaming hull.

The sudden appearance of Arashio and of Michishio was a total

surprise to the Allied ships that were retreating to northeast, but the fact

of the new Japanese reinforcements unknown the position and the composition

of the enemy force accidentally lead them to positioning between the two Allied

columns. Taking immediately advantage of the favourable position the Allied

ships opened fire against them achieving their major success in all the battle

when putting the Michishio out of action. They didn't succeed more because

they retreated rapidly off the scene.

The employment of the torpedo-launches squadron era doubtfully the best way

to finish off this battle. It was supposed that the Japanese transports (in

the case only Sasago Maru) would be defenceless and they would be easy

targets for the torpedoes from the launches. However, the limited vision range

of this kind of ships and the dark night of the battle in which they were involved

lead the third group to badly establish contact and forced to retreat in face

of such unknown conditions. In fact the launches almost didn't entered in the

Badoeng Strait and if they really have done it they could inflicted some more

damage to the Japanese ships, equilibrating more the situation, at least in

material terms. Certainly that they would present an excessive number of targets

to the Japanese destroyers and in the middle of the chaos it was much probable

that one or more torpedoes from the launches would finish to hit one Japanese

ship.

The naval battle of the Badoeng Strait was with no doubt one defeat to the

Allied forces, both in strategic, material or tactic levels. In strategic terms

the island of Bali was conquered forever by the Japanese and the various Allied

attacks failed to stop the disembarkation at Sanur Roads. On the other hand

Doorman's forces never arrived at time to avoid it, if there had been an early

Allied reaction maybe it was possible to disable the Japanese attack. So the

Japanese aerial groups find one newly base and after that they could practically

intercept all the allied reinforcements from Australia. The island of Java was

literally all surrounded and at the same time condemned herself to her own occupation

by the Japanese invader.

In material terms the Allies also paid one heavy defeat. They had lost one

destroyer (Piet Hein) and had another one seriously damaged (Stewart)

that would come to suffer the humiliation to serve under the flag of the Empire

of the Rising Sun. The ship was captured when it was in dry-dock, at Soerabaja,

when the final attack was being made to the island. The Java suffered

only minor damage but Tromp was so damaged that it was immediately despatched

to Australia for repairs. On the Japanese side the biggest casualty was the

Michishio that was crippled, the Oshio suffered moderate damage and

Asashio and Sasago Maru get only light damage. Besides the exception

of the Michishio all the other Japanese ships could return rapidly to

service. The literal loss of two destroyers and one light-cruiser in the Allies

side would certainly bring to them serious consequences in the next battle.

Much probably that if this ships and many others that were already lost during

the Java campaign were present in the final battle of the Java Sea the results

would be more equilibrated in material terms, since defeat was practically already

admitted from the very beginning of the campaign.

Respectively to the tactic field, the Allied combat strategy adopted was totally

inverted in favour to the tenacity of the two Japanese destroyers. Not even

the numeric superiority would give them something. In the other side it was

much probable that Doorman excessively trusted in artillery and ignored the

effects of the torpedoes. Without doubt that the Java Campaign was marked to

the Allies by the awful working and employment of torpedoes, but the use of

artillery means the loss of the surprise factor. Another important fact to refer

was the training and the performance of the crews of the ships. The Japanese

were highly qualified in night fighting and were strongly moralised to fight

because of the constant number of anterior victories. Nevertheless the allies

didn't equalised themselves to the Japanese in night fighting and their crews

were excessively saturated by the early naval operations and by the fact that

they were constantly in battlestations because of airstrikes. Everything failed

to the Allies in this operation, it was more favourable that they never had

to choose to fight, at least they would have spared the ships and the crews

to the final battle.

BASIC RECOMMENDABLE BIBLIOGRAPHY:

DULL, Paul S., "A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941-1945)",

Annapolis, United States Naval Institute Press, 1978.

ROSCOE, Theodore, "United States Destroyer Operations in World War Two",

Annapolis, United States Naval Institute Press, 1953

VAN DER VAT, Dan, "The Pacific campaign: World War Two: The U.S.-Japanese

Naval War, 1941-1945", Touchstone Press, 1992

VAN OOSTEN, F. C., "The Battle of the Java Sea", Annapolis, United States

Naval Institute Press, 1976

WILLMOTT, H. P., "Empire in Balance: Japanese and Allied Pacific Strategies

to April 1942", Annapolis United States Naval Institute Press, 1982

WINSLOW, W. G., "The Fleet the Gods forgot - The U.S. Asiatic Fleet in World

War Two", Annapolis, United States Naval Institute Press, 1994

However, as I already

said before, the Japanese force was detected by the Allied air reconnaissance

and calculating their destination they soon they realised that Bali was to be

invaded. In certain forms anticipating an attack to this island, the ABDA forces

had already detached to patrol the Badoeng Strait the American submarine USS

Seawolf and to patrol the north entrance by the Flores Sea the British submarine

HMS Truant was on the way. Meanwhile the Japanese continued with the division

of their forces with the disembark force entering through the straits of the

island and the backup force remaining on patrol on the Flores Sea. Incredibly

the two Allied submarines were each one of them in the same zone of one of the

opposing Japanese forces. The first to make contact was Seawolf that

detected the main force already disembarking at 0200 of the 19th of February.

The American submarine tried to make a surface attack but it was spotted by

the Japanese destroyers and forced to dive. The navigation in the strait was

precarious because the submarine didn't know the area well and ran aground in

the bottom of the strait for some time. After some attempts and frustrations

the submarine came to surface but once again it was spotted by the Japanese

escorts that advanced to attack it. In the retreat of the zone at full speed

the Seawolf fired two torpedoes from the stern tubes but they missed

the targets and exploded against the coast of Bali. Meanwhile, at the same time

that Seawolf escaped, the Truant arrived to the north area of

Bali, where the support force of Kubo was. The British submarine managed to

get close enough to this force to fire six torpedoes against Nagara but

without any impact. Discovered and pursued by the Nagara escorts, the

Truant also retreated, to Soerabaja.

However, as I already

said before, the Japanese force was detected by the Allied air reconnaissance

and calculating their destination they soon they realised that Bali was to be

invaded. In certain forms anticipating an attack to this island, the ABDA forces

had already detached to patrol the Badoeng Strait the American submarine USS

Seawolf and to patrol the north entrance by the Flores Sea the British submarine

HMS Truant was on the way. Meanwhile the Japanese continued with the division

of their forces with the disembark force entering through the straits of the

island and the backup force remaining on patrol on the Flores Sea. Incredibly

the two Allied submarines were each one of them in the same zone of one of the

opposing Japanese forces. The first to make contact was Seawolf that

detected the main force already disembarking at 0200 of the 19th of February.

The American submarine tried to make a surface attack but it was spotted by

the Japanese destroyers and forced to dive. The navigation in the strait was

precarious because the submarine didn't know the area well and ran aground in

the bottom of the strait for some time. After some attempts and frustrations

the submarine came to surface but once again it was spotted by the Japanese

escorts that advanced to attack it. In the retreat of the zone at full speed

the Seawolf fired two torpedoes from the stern tubes but they missed

the targets and exploded against the coast of Bali. Meanwhile, at the same time

that Seawolf escaped, the Truant arrived to the north area of

Bali, where the support force of Kubo was. The British submarine managed to

get close enough to this force to fire six torpedoes against Nagara but

without any impact. Discovered and pursued by the Nagara escorts, the

Truant also retreated, to Soerabaja.

As soon as the Japanese disembarking

in Bali was known, in the early morning of the 19th of February, the Allies

already had formed a plan and a naval force to attack the Japanese force. In

the lead of the Allied force was the Dutch Admiral Karl Doorman who in spite

of great difficulties and a short response time managed to group one small naval

force of three light-cruisers, eight destroyers and nine torpedo-launchers.

Nevertheless the force had to divide because of early naval operations preceding

this one, so Doorman had to move with his forces separately. In Tjilatjap was

formed the first strike force which used the Dutch light-cruisers De Ruyter

and Java, the Dutch destroyers Kortenaer and Piet Hein

and the American destroyers John D. Ford and Pope. The second

wave was made up of the Dutch light-cruiser Tromp, in Soerabaja, that

was waiting for the reinforcements of the American destroyers of Destroyer

Division 58, the Stewart, John D. Edwards, Parrott and Pillsbury,

that were coming from Ratai Bay, in the south of Sumatra. A third force of nine

torpedo-launches (TM-4, TM-5, TM-6, TM-7, TM-9, TM-10, TM-11, TM-12 and TM-13)

would leave from Soerabaja and assist the second wave in the final attack.

As soon as the Japanese disembarking

in Bali was known, in the early morning of the 19th of February, the Allies

already had formed a plan and a naval force to attack the Japanese force. In

the lead of the Allied force was the Dutch Admiral Karl Doorman who in spite

of great difficulties and a short response time managed to group one small naval

force of three light-cruisers, eight destroyers and nine torpedo-launchers.

Nevertheless the force had to divide because of early naval operations preceding

this one, so Doorman had to move with his forces separately. In Tjilatjap was

formed the first strike force which used the Dutch light-cruisers De Ruyter

and Java, the Dutch destroyers Kortenaer and Piet Hein

and the American destroyers John D. Ford and Pope. The second

wave was made up of the Dutch light-cruiser Tromp, in Soerabaja, that

was waiting for the reinforcements of the American destroyers of Destroyer

Division 58, the Stewart, John D. Edwards, Parrott and Pillsbury,

that were coming from Ratai Bay, in the south of Sumatra. A third force of nine

torpedo-launches (TM-4, TM-5, TM-6, TM-7, TM-9, TM-10, TM-11, TM-12 and TM-13)

would leave from Soerabaja and assist the second wave in the final attack.